- Home

- Christie Golden

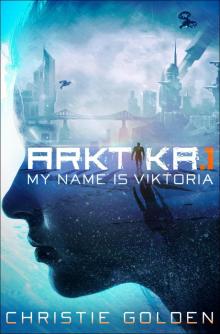

ARKTIKA.1 (Short Story)

ARKTIKA.1 (Short Story) Read online

Arktica.1: My Name Is Viktoria is a work of fiction. Names, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

A Del Rey Ebook Original

Copyright © 2017 by 4A Games Limited

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

DEL REY and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Ebook ISBN 9781524796457

Cover design: Scott Biel

randomhousebooks.com

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Arktica.1: My Name Is Viktoria

About the Author

You decided to join us! I am so pleased. It is good to see you under better, safer circumstances. Welcome, welcome indeed. I see that you have a full plate and, even more important, a full glass. I am told that one fills the belly, the other the spirit, but I would not know.

You asked me to tell you about myself earlier, but I declined. We were working then, and now we are not, and so I shall tell you my story.

My full name is Viktoria Yakovlena Morozov. I have had it for only a few years. I am named for my mother, for my father, and for winter. I died when I was twelve years old.

I have just been told that this is a scary way to start a story, but that is all right. This is a scary story, but there is hope at the end of it, as bright and beautiful as the stars when the snow stops falling and the sky is clear. And now, my friend Misha says, it is wrong for me to tell you about the ending. Ha! I am only an android, and it is clear that I have much to learn about how humans tell their tales.

Nonetheless, it is all true. I am dead, but I am here, and I will tell you about it all. So, Misha, do I start at the beginning? Which beginning? Da, okay.

If I must choose a beginning, I think that now all stories must start with the Great Freeze, must they not? Because you cannot start from the beginning without the beginning of a world, and the world we are in now was born in 2081.

You are of an age to remember the old world, at least a little, as am I. You will recall that we as a species had not been kind to our mother, Earth. We had used her, and pushed her, and taken without giving back, and at last her seemingly boundless bounty was exhausted. We had wounded her gravely, and it was we who would pay the price. Global warming had become the single greatest threat to the survival of an Earth that was able to support human life.

It is hard to conceive of now, a world like that. One of heat, when cold now presses in all around us; one of a lack of potable water, when the snow is so deep. Of air that was hard to breathe because of pollution instead of being so cold that it can damage the lungs. That was a world of blistering sun, of deserts, of air that choked, of droughts and famine. The oceans had grown increasingly acidic. By that point we had lost the coral reefs. We should have acted long ago—decades, maybe a century before that date. But such wishful thinking is an exercise in futility. The nations at that time—we had nations back then—valued profit above their planet’s future.

It was too late to repair the damage completely but perhaps not too late to mitigate it—and set a better course for going forward. We had no choice. The human race itself would perish if something was not done.

We were at a point where we could tip, as a species, one way or another. We could erupt into wars, fighting over the last scraps our poor planet could yield, like wild dogs over a single bone. We could erect barriers, retreat to our own borders. Annihilate the future as surely as if there had been total nuclear warfare.

Instead, humanity chose hope. Hope that somehow, some way, we could find a solution. It was, perhaps, the sweetest, wisest, most beautiful moment in our history. A Golden Age of science and communication. We looked at our wounded world, and every nation chose to put aside political differences so that we might come together in a unified, worldwide effort to heal it.

Knowledge that had been top-secret proprietary information would now be gladly and freely shared between countries that once had been in wars both cold and hot. It was reasoned that what good would a secret be if keeping it doomed its keeper along with everyone else? That was madness. Working together, for the good of all, was the only path to salvation for all.

I sometimes wonder what today would be like if humanity had decided to walk that path before such a degeneration of our world. Say, a hundred years earlier? Two hundred? I have extrapolated and run scenarios. I have chosen not to share them. What they have to tell us is too bleak, too sad to bear, and there is enough sorrow now, here, locked in the snows of endless winter.

I have run scenarios, too, on what happened, on the science behind the choices, on the timing, on the amounts of one thing or another.

I will tell you this much: The science was sound.

It ought to have worked.

Many ideas were proposed and rejected once the great minds of the twenty-first century put aside their differences and began to work together in earnest. In the end, the solution with any true possibility of success was geoengineering—intentional and deliberate manipulation of environmental processes on a large scale. Again…the scientists were correct in this assessment. It was the only solution.

I think now of the names that were given to the various stages of the great project, and even after twenty years, sorrow at humanity’s naiveté still lingers.

The first step was determined to be solar radiation management using a cloud-seeding compound. The creators of this new substance called it Silver Lining.

It was a clever name in two respects. It comes from the phrase “Every cloud has a silver lining.” Do you know it? It was a popular idiom, believed to have originated with two lines from John Milton’s masque Comus, written in 1634. The lines are “Was I deceiv’d, or did a sable cloud/Turn forth her silver lining on the night?” The idiom as it is commonly used, however, is not about a literal cloud but a metaphor that means that even bad things may have a positive aspect to them.

Ah. Sasha has told me that you are familiar with the idiom. My apologies.

Let me then address the second reason that calling the compound Silver Lining was particularly clever. Not only does it remind us to feel positively about the situation, which was important because hope and faith in the process buoyed spirits, it also referenced the fact that the compound would be used to manipulate clouds. You see, the solar radiation management compound would reflect the sun’s light. This occurs in nature occasionally, when a volcano’s eruption creates a layer of cloud cover. We would strive for that effect by seeding the clouds with the Silver Lining compound.

Other ideas, of course, were also in development. For instance, it was theorized that increased plankton growth would draw carbon out of the atmosphere, so work began on the creation and fine-tuning of an organometallic compound many times more efficient than simple iron.

Either of these two solutions was predicted to lower global temperatures at a steady rate. Some scientists went on record after the Great Freeze to say that everything might have been improved sufficiently if we had confined the global cooling effort to either Silver Lining or increasing iron in the oceans. But that contradicted other speculation that was backed with brutally impartial science: that even the most optimistic results would not come in time to save humanity.

Neither alone would solve the problem in time. In conjunction, however, it was theorized that the two would complement each other and produce much faster results. So, controversial as it

was, we enacted our two solutions simultaneously.

And thus was born Sol and Sea.

You are also, of course, familiar with what happened next. As I said, perhaps the greatest tragedy of all is the fact that the ideas themselves were sound.

The Sea part was the first to be put into motion. And it worked so very well. Much better, far more quickly than anticipated. It was almost a miracle—too good to be true. I believe the scientists were too happy to question, too eager to take what success they had achieved and multiply it. Hubris has been the downfall of humankind for so long, and this was no exception.

When unforeseen reactions with the environment began to occur, Silver Lining was halted. But by then it was too late.

We have lost so very much. We have lost the idea of nations and nationality. We have lost over half the population. Some say that civilization itself has been reenvisioned.

But curiously enough, we have not lost calendars. World’s End occurred on August 29, 2081, with the recording of a mutation of a red tide, a harmful algal bloom that depleted the ocean’s oxygen. But we did not realize until December 14 that it had been caused by the organometallic compound’s interaction with Silver Lining’s compound.

By then, there was nothing that could be done.

What started as a sincere and scientifically sound attempt at healing turned to harm inconceivable. I remember dropping a stone into a fountain once as a little girl and watching the ripples spread out and out and out. It was the same with our error.

So. That is the beginning of the story of this new world. I, too, have a story, one that is set against the backdrop of the Great Freeze, and I remember the world as it once was. Misha tells me that all the stories he reads to his children begin with “Once upon a time.” So I will start my story with that as well.

Once upon a time, I was a little girl of eight. I remember when this place, now a colony, was a proud, strong city with a world-renowned university. Because of our northern latitude, our obvious, immediate suffering from global warming was lessened, and living here was pleasant. Many of the professors from the university had come here from southern cities, drawn by our relatively temperate climate.

Both of my parents taught at the university; I am the proud daughter of two scientists. My father specialized in robotics, and my mother in infectious diseases. They were not part of the attempt to halt global warming, of course; it was not their area of expertise. But they were certainly interested. There was much discussion of it in my home, from the earliest mentions of the pair of proposed solutions to…well, to when the horror finally dawned.

Of course, that is not saying much. Everyone was talking about the…“project” seems to me to be too tiny, too mundane, a word to use. I shall call it the experiment. But it was particularly close to my parents’ hearts. For the first time, it seemed, science—not politics, not war, not any ruling leader—was going to save the day. They, and I, believed it was the solution.

In retrospect, I believe that once the—what is the phrase? One for when it is obvious that something is going to be one way or another? “Writing on the wall”; that is it. Once the writing was on the wall, my parents stopped speaking of it. There were a few weeks when they knew, but the rest of the world had not quite grasped just what would be coming soon. I learned later that during this brief period, when the professors in scientific fields suspected what was coming, they did something that was morally wrong at the time but that later proved to be as morally right as any decision could be.

My parents and a few others began to steal from the university.

Medical supplies. Laboratory equipment. Research. Foodstuffs. Small generators. If it could be smuggled out and put in a car, they took it.

My parents sheltered me as best they could from what happened afterward—from the panic and the violence that erupted. At first, there was a backlash against science and scientists when it was determined just how spectacularly Sol and Sea had failed. Many of the professors at the university left, but not my parents. This was their home; their daughter had been born here. They knew that they had knowledge that would be valuable. After the first wave of violence, perpetrated by those whose last hopes had been cruelly shattered, they reached out to what was left of their community, and Mamochka and Papochka helped found what has become Arktika.1.

The original colony was not located here. This site where we are now—Arktika.1, with the high safe walls and private rooms—this had not been built yet. We built it with the fruits of our labor, our courage, our determination not to give up. During those first years, those who did not flee the city and who were willing to be trustworthy and hardworking members of this burgeoning community congregated in what used to be the old travel hub.

It was a place with backup generators and tools to repair them, open areas that could house many families in one space, and so very much we could scavenge without the need to venture out into the lethal elements. Once, in better times, travelers could enter the city by flying or taking a train and then the subway to the airport or railway station.

There were also areas such as an atrium and a mall where travelers could spend their money while waiting for their plane or train. None of us live there now. The only “people” you will see there are those who mean us harm—ruthless bandits and the cruel soldiers of fortune that Citadel Security hired you to protect us from. I will come back to that, but for now, this is not part of the story.

Misha, how am I doing? Ha! I know what a gesture with the thumbs up means. Thank you!

My parents offered everything they had taken from the university when the world yet languished in blissful ignorance of what would come. They gave freely of their expertise to help everyone survive for as long as we stayed here. And once the initial anger had abated, they were welcomed with open arms. Who would not want a trained physician who was also a specialist in contagious diseases in a world where people would be forced to live in close quarters to survive? Who would not welcome an expert in robotics who could create metallic protectors to patrol in a time when simply venturing outside could kill you?

You saw some of Papochka’s early work when we drove up. Those two large robots? Ha! Yes—it had never occurred to me, but you are right—they do look like silverback gorillas! They have served us very well over the years. You will find them to be a great help to you in your job. And in the beginning, they were the ones who defended us. They enabled the colony to survive in its infancy.

And my mother…She has such a great heart, my mamochka. Her skills were tested almost immediately. She probably prevented dozens of outbreaks in those first few years and saved lives when we did have epidemics of noroviruses and influenza.

And when creatures born of nightmares began to manifest, she was there.

You have not seen them yet. But you will. And you will wish you had not.

I spoke earlier of the mutated red tides. In addition to the direct harm caused by the Great Freeze, a threat manifested in a way that was possibly even worse, at least on a more intimate scale.

Do you know what transmissible spongiform encephalopathy is? It is a disease of the nervous system. In the late twentieth century, one TSE was in the news frequently and drew much attention: bovine spongiform encephalopathy. The human form is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, popularly known as mad cow disease. It is always fatal. Ordinarily, a TSE can cause symptoms such as dementia, a loss of voluntary motor control, speaking difficulty, and personality changes, among others.

But this was no ordinary TSE. Just as ordinary algae mutated because of the reactions between the major compounds of Sol and Sea technology, a new strain of TSE developed and flourished. This one did not simply harm the nervous system. It attacked and distorted the entire body.

It most closely resembled kuru—a disease that is contracted through the ingestion of human remains, the brain in particular.

I see your eyes widen. To answer your unspoken question, yes. I do speak of cannibalism.

Aft

er the Great Freeze, of course, the world starved. We thought we had experienced famine before as the world warmed, but this…this was unspeakable. All but the hardiest plant life grew only in the very narrow band between 10 degrees north and south. And, therefore, animals that fed on vegetation starved in nearly inconceivable numbers. This far north, for example, we can grow plants only inside, and livestock is out of the question. Raising animals would consume too much of our precious resources. The only meat, then and now, was the rats we could trap or the frozen carcasses of wild creatures that had perished in the cold. Perhaps in this light it is easier to understand that in many parts of the world, no source of nourishment, not even the bodies of the dead, was ruled out.

So it was with us here. We were one of the first areas to notice the changes.

It began with the brain. Subtle, then not so subtle, personality shifts occurred. An increased proclivity toward violence. Then the body began to change, becoming less able to digest anything other than uncooked flesh. The victims’ teeth fell out, to be replaced by jagged, sharper versions. The sense of smell improved. The once-human monstrosities became so fast, so strong, even as their bodies became twisted and malformed. It is a cruel fate. Even starvation is better, I think. You could die still being who you were.

We learned that there were other communities that were completely wiped out—not from starvation or ordinary disease or violence but at the hands of other humans who had developed this awful illness. They were murdered and devoured, and those who did not die became these creatures, moving on to other areas. I say with pride but with all honesty, we would have been one such lost enclave had it not been for my mother.

As soon as anyone developed the initial symptoms, Mamochka ordered them placed in quarantine, totally isolated from almost everyone except those who believed in what she was doing and who joined her in her makeshift lab. You can see it in the airport even now, the place where she studied them, making extensive notes on their behavior, analyzing their blood, trying to figure out a cure. Some way to stop it. As is almost always the case with…well, nearly all things in life, prevention was the most effective way of curtailing the disease. After a time, the colony regained its footing slowly.

Rise of the Horde

Rise of the Horde World of Warcraft: War Crimes

World of Warcraft: War Crimes Fable: Edge of the World

Fable: Edge of the World Homecoming

Homecoming StarCraft II: Devil's Due

StarCraft II: Devil's Due Starcraft II: Flashpoint

Starcraft II: Flashpoint Allies

Allies Shadow Hunters

Shadow Hunters The Shattering: Prelude to Cataclysm wowct-1

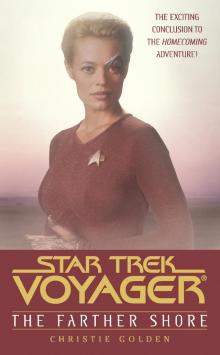

The Shattering: Prelude to Cataclysm wowct-1 STAR TREK: VOY - Homecoming, Book Two - The Farther Shore

STAR TREK: VOY - Homecoming, Book Two - The Farther Shore King's Man and Thief

King's Man and Thief In Stone's Clasp

In Stone's Clasp Jaina Proudmoore: Tides of War

Jaina Proudmoore: Tides of War Vampire of the Mists

Vampire of the Mists Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi II: Omen

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi II: Omen King's man and thief cov-2

King's man and thief cov-2 Star Trek

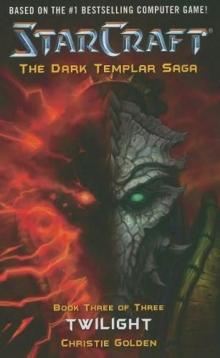

Star Trek StarCraft: Dark Templar: Twilight

StarCraft: Dark Templar: Twilight Lord Of The Clans

Lord Of The Clans ARKTIKA.1 (Short Story)

ARKTIKA.1 (Short Story) Before the Storm

Before the Storm STAR TREK: VOY - Homecoming, Book One

STAR TREK: VOY - Homecoming, Book One Shadow of Heaven

Shadow of Heaven Before the Storm (World of Warcraft)

Before the Storm (World of Warcraft) Warcraft Official Movie Novelization

Warcraft Official Movie Novelization Flashpoint

Flashpoint STAR TREK: The Original Series - The Last Roundup

STAR TREK: The Original Series - The Last Roundup On Fire’s Wings

On Fire’s Wings Spirit Walk, Book One

Spirit Walk, Book One Thrall Twilight of the Aspects

Thrall Twilight of the Aspects Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets Warcraft

Warcraft Assassin's Creed: Heresy

Assassin's Creed: Heresy Dance of the Dead

Dance of the Dead Arthas: Rise of the Lich King wow-6

Arthas: Rise of the Lich King wow-6 Assassin's Creed: The Official Movie Novelization

Assassin's Creed: The Official Movie Novelization Rise of the Horde wow-2

Rise of the Horde wow-2 Dark Disciple

Dark Disciple Ghost Dance

Ghost Dance The Shattering

The Shattering Spirit Walk, Book Two

Spirit Walk, Book Two Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Ascension

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi: Ascension Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi V: Allies

Star Wars: Fate of the Jedi V: Allies The Enemy Within

The Enemy Within Kindred Spirits

Kindred Spirits The Farther Shore

The Farther Shore Star Trek: Hard Crash (Star Trek: Starfleet Corps of Engineers Book 3)

Star Trek: Hard Crash (Star Trek: Starfleet Corps of Engineers Book 3) Twilight

Twilight